Adrian Paniwnyk

Ever since Ogof Igam-Ogam(OIO) was discovered back in April 1st 1988, it has been the hope of a rather select band of people, to find a way past the downstream Sump 4.

This sump was reached soon after the cave’s discovery, when a series of three short, but tight sumps, were passed by Croydon Caving Club's one and only cave diver, Malcolm Stewart. Beyond sumps 1-3, he explored a steeply descending zig-zagging passage which suddenly ended after a bold step and climb down in the relatively spacious Suzuki Chamber.

This chamber with its attractive calcite banding was situated on the major fault which runs almost parallel to the Afon Nedd Fechan (Little Neath River) gorge and then heads onto Pant Mawr.

Beyond Suzuki Chamber, more wet grovelling and a rather intimidating duck finally gained a section of spacious fault-controlled passage which became known as So Long and Thanks for all Fish.

Sadly, this section of passage was short-lived where after a dog-leg bend the passage dipped down to water at the infamous Sump 4.

The significance of this discovery was not lost on members of Croydon CC as the cave was trending into the western wall of the Nedd Fechan Gorge.

It was thus felt that the cave had a fair chance of intercepting the almost mythical Pant Mawr Master System which, in theory, exists in the gap between where the water is last seen sinking into Pant Mawr Pot and its main resurgence R1 in the western wall of the Nedd Fechan Gorge; R1 being approximately 1km to the south of Ogof Igam-Ogam and 4.3km to the south of where the water sinks at Pant Mawr Pot.

The water in OIO was also flowing up dip, opposite to the surface flow of the Nedd Fechan and it was therefore felt that it could be draining into the main Pant Mawr underground flow.

To highlight the importance of Ogof Igam-Ogam, two separate dye traces carried out in 2002 by Roy Morgan proved positive from OIO to R1 in less than 24 hours.

Back in the heady days of the late 80’s, when it seemed we were all footloose and fancy-free, it also seemed easy to recruit members to help with the various schemes dreamt up to further the exploration of OIO.

The first of these was to see if we could get dry cavers beyond the three perched sumps. Until then, obviously only a very select band of persons had done most of the exploration i.e. Malcolm Stewart and Peter Bolt, both cave divers. We were obviously chomping at the bit to have a look at what lay beyond.

To this end, a Suzuki generator was hired to pump out the three sumps downstream into the chamber from which it gets it's name. Eventually, self-syphoning tubes were installed to empty the sumps. The problem here was that it took about two days to achieve this as numerous separate trips had to be made. I must have been keen in those days as I used to try and speed things along and go down in the middle of the night, when I thought that a sump might have emptied. The problem here was that on numerous occasions the syphoning had not worked. The only thing which could be done was to restart the syphon and then head back to the cottage for some sleep.

On 18th June 1988, the first attempt at diving Sump 4 was made by Malcolm Stewart. However, things did not go very successfully as Malcolm wrote in the logbook:

"Progress backwards extremely difficult – everything catching and snagging, very hard finding passable way through wide bedding plane sump in absolutely zero viz. At 25 feet in (depth a couple of feet) and no sign of air whatever had a flake of some sort fall on my legs. Totally turned off, exited the sump with considerable difficulty - I will not be going back in here - anyone else is welcome to it."

On 15th July 1989, numerous members of Croydon descended on Sump 4 to hopefully pass it by bailing the water into a dam built of both bin and fertiliser bags 4-5 feet in front of it. George Pankiewicz wrote in the logbook afterwards:

"The total level we dropped must have been 15 inches max. over a period of two odd hours. However, as the water got to the top of the dam it rather unfortunately broke up, so we pulled out the large green bag on the right side to watch a fine cascade rush through the sump."

Based on the rate we had dropped the sump level, we assumed at the time that the sump was quite short. However, in 2018 this assumption was to be proved very wrong.

George also wrote at the time: "an alternative route is along the left wall but very silty. Dry passage further on could be seen by Adrian". Trying to remember back to that day many years ago, I cannot remember seeing any dry passage. I suppose back in those days I was a bit more optimistic and somehow my brain had translated flat-out watery crawl into dry passage!

Dam building at sump 4 5th July 1989.

From left to right Richard Rolfe, ?,

Adrian Paniwnyk. (Photo by Steve Wray)

Strangely enough by the 13th August 1988, Malcolm seemed to have forgotten about his plan of not returning to dive Sump 4. Either that or we had pestered him quiet a lot!

This time the dive was combined with some dam building but once again the claustrophobic confines and the silted out zero viz. conspired to result in little more progress than last time. The only advantage of our bailing was to produce a small air bell within the sump where Malcolm was able to check his gauges.

Prophetically, Steve Goodall wrote at the time that Sump 4 "Will need a dive down the left wall."

All dives prior to those made in 2018 had started out going down the right-hand wall but it was a dive starting on the left wall of the sump pool which was to provide the long sought after key to the sump. As is the way with most new cave discoveries, except for a few minor finds and interesting observations, things started to slow down.

However, on a solo trip on 1st July 1989 I wrote: "entered chamber inside Snorer’s Annexe choke mentioned by Phil Brooks on 14th June 1988 and pushed through small hole on east side of chamber, following water up through boulders, came across numerous coke cans, paint tin lids and large sticks. Does this mean anything?"

It thus seemed clear there was a way to the surface, but at the time it was impossible to follow the water as the passage at the time ended in a choke of calcite boulders.

14th July 1989 was certainly made memorable as Chris Crowley almost managed to drown himself, whilst attempting to free dive back through Sump 3. Underwater, the dive line became caught round his neck, noose like. Fortunately, there was just enough slack in it for him to reach air space and I was hanging around by the sump pool to hack it away from his neck!

On a more sedate note, afterwards we located a small water-worn tube in the west bank of the gorge downstream from the original OIO entrance.

I wrote at the time: "Quite possibly may connect with the boulder choke in Snorer’s Annexe but will require a flat out dig to remove gravel." Numerous trips into what became known as the Dry Way Dig then followed. However, it quickly became clear that other more stubborn things than scoops of gravel would have to be removed. Around a corner we quickly hit a tight bedding which would not succumb to being enlarged with a lump hammer.

Fortunately, Clive Jones of SWCC helped us out by chemically enlarging it. Beyond the bedding, a small chamber was entered, enough to hold, what Paul Stacey described as, "two friendly midgets".

However, the roof appeared to consist mainly of loose looking boulders. When one of these boulders fell on my head without me provoking it, even I started to lose enthusiasm and move away for possibly easier options.

The dig lay abandoned for about ten years, until in the early 2000’s Tony Donovan and Roy Morgan, who I was now doing some work with, became interested.

In a very determined manner, using scaffolding and chemical persuasion, they managed to punch a way through into the upper reaches of the Snorer’s Annexe. With a new entrance bypassing the first three sumps it seemed initially that more progress in this cave would now be made. Indeed, Martin Groves did make another dive in Sump 4. However, again diving down the right hand side, no more progress in the nasty bedding was made beyond what Malcolm had achieved. And then again, people quickly began to lose enthusiasm for work in OIO.

Tony, however, did start to do some shoring work in the choke I had climbed up through on 1st July 1989. This choke is some 10 metres from Roy and Tony’s original scaffolding breakthrough dig. However, this was never finished; the pile of rusting scaffolding bars lying on the surface bore testament to this. It was not totally surprising that it was abandoned as it had always looked dangerously loose.

Later I heard that Tony’s scaffolding breakthrough dig had either collapsed or blocked itself up with flood debris. So once again Ogof Igam-Ogam was to enter one of it's long periods of inactivity.

It was not until Whitsun 2017 that it was decided to check out the state of the Dry Way Entrance. Malcolm expressed an interest in re-diving Sump 4, provided we could get that far. Expecting the worst, we were pleasantly surprised to find that, apart from clearing out the usual flood debris in the entrance crawl, the way on was reasonably clear. We progressed onto the calcite chamber and the way into the loose choke where Tony had started but not finished his scaffolding.

The choke was already living up to it's nasty reputation, as an assorted collection of rocks had fallen onto the scaffolding put up at it's start. These were quickly pulled out of the way and after a moment of hesitation I squeezed feet first into the random jumble of blocks to see if a way on still existed. Sliding downwards, I was quickly brought to a halt with the view through my feet of a massive boulder with a scaffolding bar bent like a banana beneath it. It was difficult to determine whether the boulder had fallen onto the bar or had been put in like that, but after a bit of careful looking around it was clear that collapses within the choke had rendered the original route through it impossible.

Rather despondently, I returned to Malcolm and Chris to give them the bad news. It seemed that there would be no quick and easy route back to Sump 4.

Strangely enough, I decided to return a few weeks later on a solo visit - Chris had a cold – to see if something could be salvaged from the situation. Reaching the spot where I had squeezed down into the choke, I quickly realised that things had gone from bad to worse.

Several large blocks had slumped into the hole I had previously been through a few weeks before. It was clear that if this had happened whilst we had been in there we would have possibly been trapped, or at worst squashed flat! I must admit I felt despondent. It seemed to me that there would be no way of regaining the main cave via the Dry Way Entrance.

To kill a bit of time, I climbed up into the decorated chamber which lies above the choke. I soon reached the back of the chamber and in a bit of a daze saw myself staring down into the small fractured rift which I had noticed many years ago. And then it hit me like a bolt from the blue, that if somehow the rift could be enlarged, we would have a fair chance of bypassing the collapsed choke below. I started by pulling out a few rocks and then by throwing a few pebbles down it at the right angle, I occasionally heard the sound of one falling into a void below - music to my ears.

In an instant all my negative thoughts had been dispelled as I realised that if a return was made with the right tools, we would have a fair chance of succeeding. On a wave of renewed enthusiasm, I exited the cave to tell anybody that was interested the good news.

On August Bank Holiday 2017, Malcolm, Chris and myself returned with all the digging kit to hopefully enlarge the rift which was only a few inches wide.

However, using the tried and tested technique of "knocking six bells" out of it we were soon breaking out large lumps of rock. Fortunately, the rock being situated on a fault line was already pretty broken up anyway - in most circumstances in good solid limestone we would have not been successful. Further enlarging the rift, it soon became clear that it belled out quickly into a chamber below. Enthusiasm began to rise as this was certainly the chamber on the far side of the collapsed choke.

We now knew that we were close to getting back into Ogof Igam-Ogam. By the end of the digging session we had tried every technique in the book including the rather unnerving experience of not having some Hilti caps go off and we still had not managed to enlarge the rift enough to fit through. There appeared to be a more solid piece of limestone below us which would be more difficult to break up. As well as this in the confined space of the rift we were unable to get a decent swing with the lump hammer. Time was getting on now and feeling quite tired after a day of serious boulder bashing, we decided to try a few snappers out on the rock below. Drilling two shot holes, I hoped, would see us past the obstacle.

After the usual fiddly bit of charging the holes and wiring things up, I retreated, laying out the wire which would be used to set the snappers, from a distance, or in this case not a great distance away as there was not a great deal of flex on the reel!

Hiding behind a suitable bulge of calcite and hoping for no misfires, I jabbed the end of the wires in the terminals of the battery.

Fortunately, I was almost instantaneously greeted by the soft whump sound of the snappers going off. It was not, by any means, the loudest bang I had ever heard, so that as I raced back to the entrance to avoid any fumes, I hoped that it had done its job.

prior to trip on 17th Feb 2019. Chris Crowley, Helen &

Malcom Stewart and Adrian Paniwnyk (pic: Helen Stewart)

Malcolm and I returned on the following day. Clearing the debris away we soon realised that we were not going to be able to descend straight away, so a short while later we were again bashing away with the trusty lump hammer.

However, it soon became clear that this time the rift would soon be large enough to pass. Eyeing up the size of the hole, I suggested to Malcolm, being the thinnest, that he might like to have a go at squeezing through.

After tying a rope round a large block to act as a hand line, Malcolm slipped down - gravity assisted - into the void below. I now felt duty bound to try and follow, but as I descended all too easily it did occur to me that getting back might be more difficult from going down.

It was now clear that we had regained the chamber first entered by Phil Brooks in 1988 and that we were back in OIO. We now felt duty bound to go for a tour of the cave ,but as we were wearing only dry gear, we only made it to the start of the duck in So Long and Thanks for all the Fish.

Later, looking around Suzuki Chamber we found the old plastic bilge pump which had been used to start the syphons in sumps 1-3.

It had obviously been swept down there by some major flood. We took it out as a trophy to show Chris and to prove we had made it back into the cave.

All in all, a great day of caving had been had, even the squeeze back through the breakthrough point had not been so difficult due to a handy ledge just below the vertical squeeze.

With the ball quite firmly in Malcolm’s court, plans were drawn up for a dive in Sump 4 on the weekend of the Fireworks 'do' 2017. However, to ease the progress of kit through the flat out grovels at the start of the cave, Chris and I made a trip with plugs and feathers to chip away the top of the boulder in what Chris described as the "dreadful switch back section that was very back wrenching". Further hammering out of the weak tufa material just beyond greatly eased progress through the difficult section.

Gareth Davies in the westerly trending passage

beyond the aven in Thirty Year Itch

(pic: Malcom Stewart)

No diving was, however, done until the two short climbs just before Sump 4 were re-climbed, in the hope that a bypass to the sump might be found. If we had been up them, we had certainly in the intervening years forgotten what happened at the top and the accounts in the logbook were inconclusive.

The first muddy climb directly above the sump was quickly shown to end in an impossibly tight rift with no draught. We also had a go at the climb on the s-bend in the passage some 20 metres back from Sump 4.

After two bolts placed with me balanced on the top of Malcolm’s shoulders, a flat-out passage was gained which quickly got too tight after about a body length. There was however a slight draught running into the passage at the top.” A compass bearing on this passage later revealed that it appeared to be running back above the stream way below - on the day of the climb the draught was also felt running back through to the entrance.

The first dive into Sump 4 was on 2nd December 2018. This time it had been decided to focus on the left side of the sump as all previous dives on the right had not been successful.

Finally reaching Sump 4, I must admit I felt a bit down beat, for odds on the previous dives had been correct in ascertaining the sump was indeed zero viz. and tight and I had no reason to assume that Malcolm’s dive today would be any different. I also felt somewhat unhappy about him being put through the distress of having to dive the sump again. If Malcolm was feeling worried about the forthcoming dive, he certainly wasn’t showing it as he edged feet first into the sump pool.

The water did look remarkably clear, but I realised that in the low confines of the bedding such good visibility can be snuffed out in an instant. However, totally unexpectedly, as Malcolm wrote in the CDG Newsletter, "most of the mud seemed to have disappeared in the thirty years since the diver was last here and comparatively easy wriggling progress between solid roof and compacted gravel floor was possible".

Malcolm quickly came to the end of all the available dive line he had brought about 5 metres. This line had been attached to a short length of modified scaffolding bar called a Derbyshire Tube designed to allow for the controlled laying of line in poor visibility conditions.

However, on this day the magic cave fairy had seemed to have cast a spell and as he came to the end of the line he was “stunned to look between his feet in very good visibility in what looked like a slightly larger continuation”.

It seemed amazing that, after several dives previously, he had managed to find the way on. Aside from the fact that no dive down the left side of the sump had been made , another possible explanation is that the dam built in front of the sump pool had helped prevent some thirty years of silt entering the sump, and with regular floods since then, had helped to flush out the tight bedding at the start.

Obviously feeling more confident of making a safe exit, Malcolm entered the sump head first on his next dive. He reported in the CDG Newsletter, "there is a definite low section at about 5 metres but beyond this point the passage expanded". It had again been assumed that the sump would be short, so after laying out approximately 9 metres of line from a Derbyshire Tube, with no end in sight, a return had to be made to collect a line reel. Malcolm wrote "the diver continued forward in roughly eye-shaped passage about 2 feet high. The route undulated round a series of gentle corners, descending under arches and rising over gravel and sandbanks".

Eventually, after approximately 38 metres, even the line on the reel run out and after a brief foray beyond the line, with no sign of the sump surfacing, Malcolm was forced to retreat.

By 17th February 2018 we had told Chris about Malcolm’s success in finding the way on in Sump 4. So with Chris keen to pay a visit to Ogof Igam Ogam, and with Helen Stewart and myself in support, we had no problems getting Malcolm’s kit to the start of the sump. This day was to prove a most eventful one for more than one reason.

Passing his previous limit of exploration, after what he thought seemed like a very long time, Malcolm surfaced in a tall muddy air bell and shaft. But with no easy way to climb this the only thing to do was to carry on diving. After a further few metres another low air bell was encountered, where when he stuck his head up, the sound of running water could be heard. Rather than investigate the source of the sound, Malcolm decided to press onwards in the sump, but almost immediately the nature of the passage changed, becoming more low and awkward.

Then in the deteriorating conditions, Malcolm encountered a strange metal object. It took a moment to realise that it was the rusting remains of the coal scuttle as Malcolm puts it, "borrowed many years previously, when the Cottage Warden's back was turned and used to bail the sump" (see third picture).

A few metres further on, Malcolm encountered more physical remains of the sump bailing exercise, this time a mass of old plastic sheeting. Carefully passing what Malcolm described as the “plastic menace”, a slightly larger area with a small air bell was encountered. It was at this point that Malcolm decided to commence his return, for as he said he was "conscious that he was a long way from home and had a lot of non-belayed line behind him".

Returning through the middle air bell mentioned previously, he was intrigued to find out where the sound of water was emanating from. It appeared to be coming from a low duck on stream left and when this was passed it brought Malcolm up into the base of a three metre diameter chamber. When he looked up, I imagine he was also stunned to see an aven soaring up above him, so high that the top could not be picked out.

Down a flowstone covered wall on the opposite side of the shaft, a cascade of water was falling over a lip some 5 metres up - enough to produce the sound heard earlier on. Things looked even better when a tall rift passage was spotted on the far side of the aven chamber. On this day, Malcolm followed this ruler-straight passage in a westerly direction for approximately 30 metres, until he was forced, still wearing his diving kit, onto his hands and knees by a lowering of the roof. Beyond he said: "the passage appeared to continue open, but in deference to his Sherpas and his own imminent hypothermia, the diver again started his return."

Meanwhile, whilst Malcolm had been trying to locate the Pant Mawr Master system, Chris, with Helen, had been digging a hole in the bottom of the stream bed upstream of the sump to stay warm. He also had a theory that the sump might disappear down the hole plug-like, but rather strangely this did not work, maybe the hole just wasn’t deep enough! I was taking the more relaxed approach, perched on the remains of the dam, staring into the murky sump whilst contemplating the meaning of life.

However, eventually the numbing cold in my feet stopped such idle thought and forced me into activity. Although I was wearing a wetsuit, I was only wearing woolly socks so I spent a bit of time wringing the water out of them, knowing full well that my feet would get wet again when I had to put them back into the water. The job of the cave dive Sherpa is of course filled up with exciting moments like this!

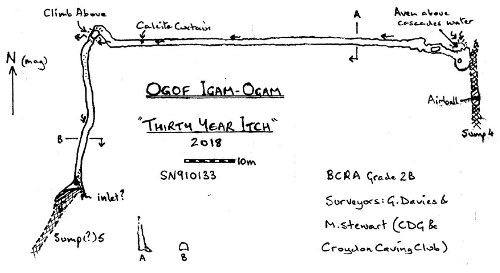

After some forty minutes away, Malcolm returned to give us the good news that, after some 30 years since the cave was discovered and several previous attempts made, Sump 4 had finally been passed. It was for this reason that Malcolm quickly named the new section of cave beyond Sump 4 “Thirty Year Itch”.

However, as mentioned previously this was not the only strange occurrence of the day. Malcolm was just packing up his diving kit when I heard a deep, ominous sounding bang which appeared to emanate from back down So Long and Thanks for all the Fish. It lasted for about ten seconds, starting out quite loud and then dying away. For a moment I thought that my ears had been deceiving me, but observing the worried-looking expressions on everybody’s faces this was obviously not the case.

A brief discussion then followed which begun with something like "What on earth was that?" and then moved onto possible causes. I must admit it did occur to me that as we were some 30 metres below the level of the river bed the cave was now starting to flood. Having read about numerous instances of flash flooding in caves was doing very little to calm my nerves. After what seemed like an eternity, with one eye fixed on the stream level to see if it was going up, we started out. I shot off as quickly as was physically possible, which was not particularly fast as I was having to coax and cajole a 5 litre cylinder through the flat-out grovels which punctuate So Long and Thanks for all the Fish.

Thrashing and flailing through the watery confines of the canal, half expecting at any moment to be greeted by a frothing wall of water, was not one of the most pleasant experiences I have had. Reaching the far side of the canal, trying to catch my breath, but with no sign of increased water levels, I started to calm down somewhat.

I waited for Helen to catch me up and when we reached the junction at the start of Coffin Passage it was clear that if anything the reverse of the cave flooding was occurring. For looking closely at the small stream, which was flowing down this passage, if anything it's flow had decreased. Strangely enough, this did little to calm me down, it almost immediately set my mind racing for some other possible reason for the sound we had heard. Clutching at straws, it now occurred to me that a major collapse somewhere within the entrance series chokes might have been loud enough to be heard down at Sump 4.

So now, fearing that we might be effectively sealed within the cave, I once more had something to worry about. However, passing through the boulder crawls on the fault, we were greeted by no collapses or even the slightest sign of movement. With the last few bends of the cave in front of me and with the first few rays of sunlight beginning to dispel the darkness, I knew that we were going to make it out.

Then, with my head poking out the low entrance, I was greeted by the sight of no flood swollen stream ready to envelop the entrance. Then turning over and looking up at the sky, apart from the odd rather angry purple coloured cloud floating past, it looked as if nothing had changed since we had descended.

And so the incident of the loud bang down OIO might have been forgotten about. Getting changed and making light of it, Chris even suggested that it had been the Russians nuking Cardiff!

However, on returning to the cottage in Ystradfellte and speaking to some of the locals, it soon became clear that the bang had not been a figment of our imaginations. In fact, our bang had made the national news and turned out to be a shallow, minor earthquake with a magnitude of 4.4 and epicentre 20 km NNE of Swansea.

I imagine with a stronger quake our safe exit from the cave might not have been assured! Even though it was weak it was apparently felt over much of S.W England, Wales and as far east as London - it's occurrence reported in the news over the whole of the UK.

So much so, that my wife, having heard about the earthquake and being unable to contact me, had started worrying.

Since last February, various trips beyond Sump 4 have been made to try and extend the cave further. The tall rift passage leading off from the base of the aven in Thirty Year Itch, although starting off in a spacious manner, quickly degenerated to a hands and knees crawl. The passage having turned to the south leads to what Malcolm describes as a low committing sump come duck. I say duck as it has several unusable low air spaces throughout it's length. What has become known as Sump 5 is, according to Malcolm, very reminiscent of the long canal section at the start of So Long and Thanks for all the Fish.

However, looking at the photo taken at the start of Sump 5, it looks, in my opinion, even wetter and lower! Pushing Sump 5 has not been without its difficulties. On the first dive here, a sudden dramatic equipment failure and a loud bang resulted in the almost instantaneous loss of air from the cylinder being used at the time and dictated a prompt exit from the sump, Malcolm then had to dive back through Sump 4 with no cylinder in reserve.

A further dive was also plagued with more equipment problems. With free-flowing regulators it appears they do not like being ground through the heavy mix of silt and cobbles in the low bedding.

Once in the sump it possesses a series of zig-zag corners, to a point that Malcolm believes that it's general direction has switched from a southerly to a north westerly direction. In conclusion, as Malcolm says in the CDG Newsletter, the end of the sump remains open but "will need a further visit with more courage".

Over a series of three climbing trips, the aven in Thirty Year Itch has been climbed by Gareth Davies and Malcolm. Rather amazingly, considering we are not in the Yorkshire Dales, it turned out to be some 35 metres high, which goes to show what can be lurking beneath your feet! Sadly though, "The two ends at the top, one chocked with boulders and the other a narrow heavily calcited rift are not meant to be promising".

Apparently, the best formations so far found within OIO are found at the top of this aven, but owing to the obvious obstacles that need to be passed, I can’t imagine there will be many people rushing in to see them.

Due to exceptionally dry weather when the aven was climbed, no water was flowing down it at the time. However, in wetter weather it acts as an inlet into the system. The source of this water is currently unknown, but maybe it is a relatively short-distance drainage from nearby sinks at the limestone/grit junction.

For example, up dip drainage from Ogof Derwen or a sink almost directly above OIO. There is always the chance that it is coming from further afield, perhaps Sarn Helen sinks or even Hole 18? which would be very interesting if proved correct. According to Malcolm, another lead goes off where the westerly trending passage degenerates to a crawl and turns to the south.

The usual very muddy and slippery climb must be negotiated here to gain approximately 30-40 metres of unsurveyed passage that is believed to be heading in a westerly direction.

Apparently, there are suggestions of ways on here either by digging or further climbing. In order to try and fix some of the positions within the cave to the surface, a radiolocation exercise was carried out in September 2018. Three points within the cave were selected, the first being some 20 metres upstream of Sump 4, where the only dry, level spot for the transmitter could be found.

On the surface this radiolocation point was seen to be near a line of trees to the rear of a ruined building, Cefn-ucheldref, which is shown on Ordnance Survey maps. The most interesting thing to be noted about this first radiolocation point is that it does not match up with the OIO survey conducted in 1988 - see map below.

The surveyed position is some 20 metres to the south west of the first radiolocation position. Rather ironically, it now appears that the divers’ survey beyond Sump 4 is more accurate than that carried out by dry cavers prior to Sump 4, usually the opposite is the case.

The error could have been caused by various factors, the fact that a survey leg was missed out in the zig-zags of the original entrance series prior to Sump 1 would not help or even the grim nature of surveying through the duck and flat out crawl of So Long and Thanks for All the Fish. Obviously, a new survey through the Dry Way entrance down to Sump 4 would solve the problem.

The only surveying carried out in the Dry Way crawls were carried out by Roy Morgan with his handheld compass and his one metre measuring stick. The best current estimate for where the water goes off in Sump 4 is approximately NGR SN 90948 13558.

Radiolocation point 2 which is at the base of the aven on the downstream side of Sump 4, is seen to be in the open field to the rear of Cefn-ucheldref and a few metres to the east of the Sarn Helen track. About 8 m from the footpath finger-post at approximate NGR SN 90910 13555.

The map shows that in a straight line the sump is less than 40 metres apart but underground the total dived distance is about 80 metres due to it weaving about under water. There are no surface features in the field i.e. depressions or shake holes which would indicate that this aven is below the surface.

Radiolocation point 3 was on a mudbank at the start of Sump 5. On the surface it was shown to be some 50 metres of Cefn-ucheldref to the west of Sarn Helen and within the forestry. Very approximate position fix NGR SN 90835 13538. The received signal at point 3 is described on the map as “amorphous” and it seemed impossible to get an accurate position fix.

Maybe this is due to the increased depth about 10 metres gained as you travel from position 2 to 3.

Comparison of original OIO survey with Malcolm’s Thirty Year Itch

survey added and actual points within cave as revealed by

radiolocation. Yellow pins are radiolocation points.

Scale bar above grid reference is 10 metres.

Fortunately, Sump 5 lies above some definite surface features, a line of shake holes at the gritstone/limestone junction which runs down to Ogof Derwen. We have done a bit of digging in one shake hole closest to the amorphous zone which appears to offer the best prospects.

However, we have not made much progress. It is some 70 metres down to the passage in front of Sump 5 which is a bit off-putting and much scaffolding and breaking up of large gritstone boulders will be required. Geologically it is difficult to say at this moment whether the new section of passage in Thirty Year Itch is still on the major fault which has aided development to the start of Sump 4 or has moved away from it.

Reading an article about Tatham Wife Hole in Caves and Karst of The Yorkshire Dales Volume 2 (p354-355) it appears that fault zones can be quite wide and complex, with even the fault dip varying along it's course and the length of the fault being far from straight. The main conclusion from all the above is that explorations within the cave have not concluded.

This is both good and bad news. Bad, in that nobody, as yet, has had the pleasure of finding the main flow from Pant Mawr Pot, but good for me, if I manage to get myself through Sump 4. Hopefully in the not too distant future there might be something left to explore! I just hope that I do not get too old and decrepit or scare myself too much to achieve this!

The history of the exploration of OIO has very much been a case of one step forwards and two steps back, but I really do think this time that the goal of finding the continuation of Pant Mawr Pot is close.

References: Cave Diving Group Newsletter No. 208,209 Blue Croydon Caving Logbook 1987-1989 Waltham, AC, DB Brook, 2017. Caves of Ingleborough. Caves and Karst of the Yorkshire Dales. Vol. 2. BCRA pp 354-355